Pleased to read this fair article from the Age in Melbourne giving (I think) a realistic picture of palliative care.

And…. no pictures of hands!

What did you think?

Thanks Miki Perkins @perkinsmiki

Pleased to read this fair article from the Age in Melbourne giving (I think) a realistic picture of palliative care.

And…. no pictures of hands!

What did you think?

Thanks Miki Perkins @perkinsmiki

Sarah Winch, The University of Queensland

On average 435 Australians die each day. Most will know they are at the end of their lives. Hopefully they had time to contemplate and achieve the “good death” we all seek. It’s possible to get a good death in Australia thanks to our excellent healthcare system – in 2015, our death-care was ranked second in the world.

We have an excellent but chaotic system. Knowing where to find help, what questions to ask, and deciding what you want to happen at the end of your life is important. But there are some myths about dying that perhaps unexpectedly harm the dying person and deserve scrutiny.

Read more – A real death: what can you expect during a loved one’s final hours?

Another insightful article from Dr Ranjana Sriastava, a Melbourne medical oncologist and writer, encapsulates my recent experience as a palliative care doctor on the frontline between hope and dying in a cancer centre.

The anticipated miracles of cancers dissolving before our eyes are common enough for patients and doctors to push on with expensive, sometimes self-funded treatment (at great cost) in preference to the needed preparation by patient and family for dying. For a patient and family perspective, skip down to the comments after the article and read HugiHugo’s description of his wife’s last months while undergoing treatment.

A patient with widely disseminated and aggressive melanoma having immunotherapy grunted at me in frustration last month. “Listen,” he said, “they are all high-fiving over there in the oncology clinic. Why do you want to talk about end of life stuff? It’s really confusing.” Pretty appalled at the idea that we were giving the patient mixed messages, I was fortunate to be able to do a joint consultation with the patient’s medical oncologist to nut out our different perceptions. Unfortunately for the patient, his oncologist confirmed that the treatment was very unlikely to be a miracle and most patients in his situation would live less than a year. To say that the patient was shocked was an understatement. Had he not been referred to my team for symptom management, this conversation would have happened later – or never.

Evidence is emerging that outcomes of immunotherapy in patients with poor performance status are very unimpressive. Patients with poor performance status had been excluded from initial trials.

Where does the deficit in our communication of hope lie? Is it in the delivery by the doctor? The reception by the patient? A bit of both? How can we accurately respond to the portrayal of immunotherapy in the media and social media as a miracle cure, and allow for the possibility of benefit without downplaying the risks?

Sonia

Just getting ready to head to Adelaide for the Australian palliative care conference 2017….

Getting excited!

The smart phone app is really good and I am not just saying that cos Elissa and I are nearly at the top of its Leaderboard.

Go on, check it out!

Who is coming…..?

http://pca2017.org.au/getinvolved/

See you there?

Sonia

An excellent post from a person who knows about the old battle metaphor for cancer. Cancer is not a failure of will or morals.

Thank you CM!

Some of you may have seen 60 Minutes on Sunday evening. It featured the story of ‘Patient 71″, a woman named Julie Randall who was diagnosed aged 50 with metastatic melanoma. She found a place on a US clinical trial and is now in excellent health. There is much that is great about her story. She was very much her own advocate and aggressively sought out treatment options. But the rhetoric around the story was less than great.

The 60 Minutes Story ran a very strong line that Julie refused to die and leave her teenage children. As if it is really a choice. I now know far too many mothers and fathers who have died leaving children much younger than Julie’s. Not one of them wanted to leave their children. I suppose I shouldn’t expect much more of 60 Minutes than the trite and cliched. And yet it annoyed…

View original post 403 more words

CareSearch has created online resources that will help build a path of cultural capability and understanding for supporting care with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Ensuring that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients feel culturally safe and receive culturally responsive care is a key responsibility of every health care provider.

Guided by an expert advisory group comprised of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people representing various organisations within the health sector across Australia, CareSearch has created online resources that will help build a path of cultural capability and understanding for supporting care with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Care pages include information for providing culturally appropriate care for all health care providers, the Aboriginal health workforce, and the wider health workforce; share information with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, their families and communities; and provide information on finding relevant research and evidence. There is a strong emphasis on the person’s care journey and how members of the health care workforce join their journey along the way.

You can access the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Care pages at http://www.caresearch.com.au.

Contact caresearch on caresearch@flinders.edu.au

Acknowledgements: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Reference Group, PEPA & PCC4U (The Collaborative), Leigh Harris, Igneous Studios

It may be a favourite scene from ‘Six Feet Under’ – the cult TV drama series depicting a family-run funeral home in Los Angeles. Or, it might be an iconic image of those prominent funeral companies that can seem to dominate the industry. If, however, you are currently in the throes of organising a funeral – chances are you may not really know what to think, or where to go in terms of navigating this very difficult passage of time.

As a social worker or nurse working in palliative care, you may be unsure of what resources are available to help support families’ decision making during a time of mourning. That’s where a novel funeral home comparison site can be of great assistance – you may find what you are looking for Gathered Here.

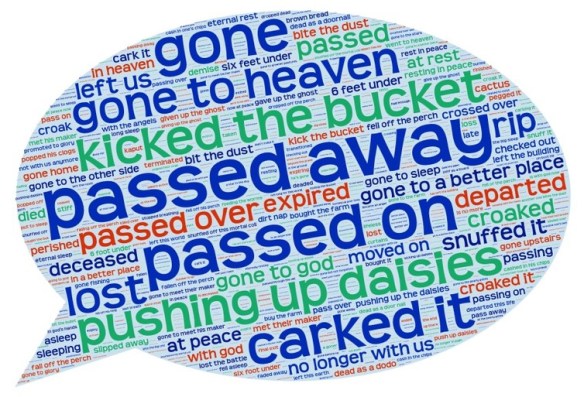

I learned a few new euphemisms for dying in this Conversation article. Confession time – it’s kind of my job to use the “D” word but even I, as a palliative care doctor, can find it awkward. But if we hide behind phrases like “passed away”, “gone” or “lost”, we contribute to confusion in some and participate in death denying.

If health professionals use euphemisms, they need to consider whether patients really understand what they’re trying to say. The article concludes that “Euphemisms have their place. But being able to talk openly (and clearly) about death and dying is important as it helps normalise death and avoids confusion.”

If health professionals use euphemisms, they need to consider whether patients really understand what they’re trying to say. The article concludes that “Euphemisms have their place. But being able to talk openly (and clearly) about death and dying is important as it helps normalise death and avoids confusion.”

Happy palliative care week!

Sonia

Embarrassingly, I didn’t know about this until I heard it at a RACP conference last week.

EVOLVE is a physician led initiative to ensure the highest quality patient care through the identification and reduction of low-value practices and interventions. Many specialties have created their own lists.

ANZSPM, the Australian and New Zealand Society for Palliative Medicine, have nominated 5 interventions which they recommend against in palliative care.

Curious?

Palliverse has heard about two PhD scholarships in the area of improving psychosocial support and education for people with cancer and their carers, at Curtin University in Perth, WA. Scholarships are available to health professionals (particularly nurses and radiation therapists). For more details see the Curtin University website.